The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recently proposed a new reporting regime to increase transparency and efficiency in the securities-lending market. The SEC seeks to accomplish this by requiring anyone who loans a security on behalf of himself or another person to report material terms of those loans (and related information regarding the securities on loan) to a registered national securities association (RNSA), namely the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). As we have discussed, the proposal is a sweeping change and a somewhat novel approach to bringing securities lending out of the dark. While the merits of the proposal’s approach will no doubt be thoroughly scrutinized and debated, so too should its cost and who will bear that cost.

The point of the SEC’s proposal is to “supplement the publicly available information involving securities lending, close the data gaps in this market, and minimize information asymmetries between market participants.”[1] While the potential benefits would seem to flow to all participants in the securities lending markets, the SEC’s choice to place the reporting burden on lenders and their agents also burdens those loan participants (lenders particularly) with nearly the entire cost of compliance.

Some gaps in the SEC’s robust analyses.

The cost-benefit and economic analyses of a proposal are where the SEC attempts to quantify its reasoning process and reveal which aspects of the regulatory issue it has taken into account.[2] And since some regulations have been challenged successfully based on the quality of these analyses, the SEC takes care with them. But, the SEC found its assessments of this proposal hampered by some of the same siloed and incomplete data and opaque transaction chains the proposal seeks to remedy.

“[B]ecause the Commission does not have, and in certain cases does not believe it can reasonably obtain, data that may inform the Commission on certain economic effects, the Commission is unable to quantify certain economic effects.”[3]

In other instances, like its analysis under the Paperwork Reduction Act, the Commission did not have data regarding the number of lenders, agents, or reporting agents as potential respondents and was forced to employ reports on Form N-CEN and other methods as proxies.[4]

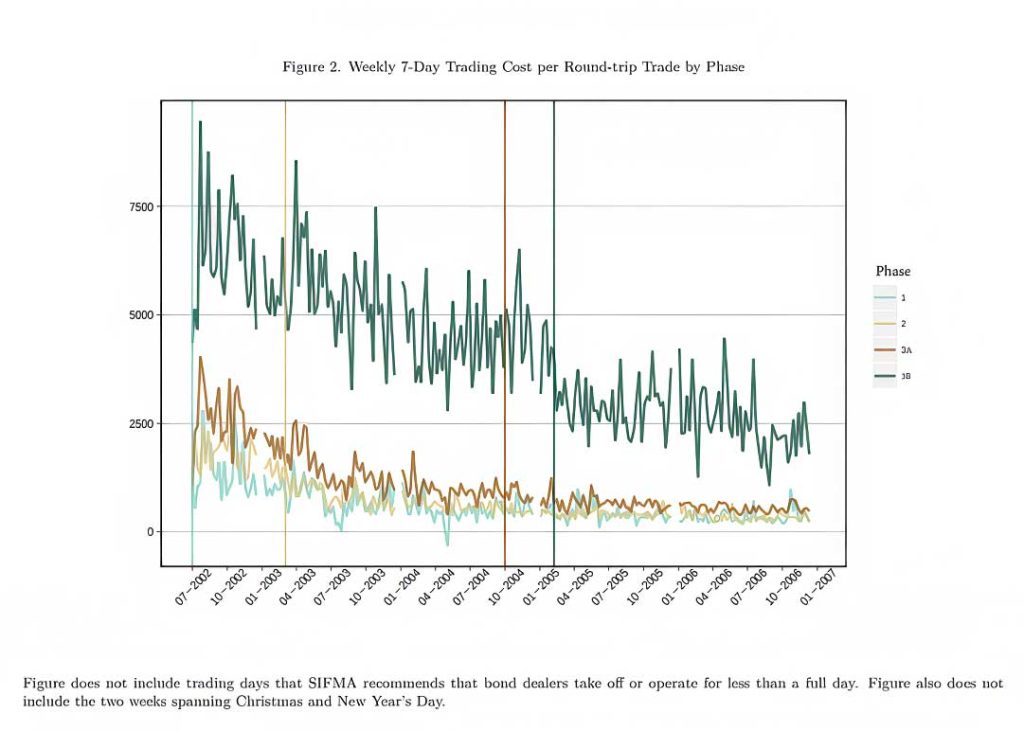

Despite these gaps in available data, the Commission concludes that the benefits of increased transparency in securities lending would be considerable, and would be supported by historical precedent. The Proposing Release cites the effect the introduction of TRACE (FINRA’s Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine) had on the transparency and pricing efficiency of the corporate bond market as precedent for what could be in store for securities lending markets as a result of supplying market participants with better and more timely data.

“The Commission preliminarily believes that the proposed Rule would result in increased transparency in the securities lending market by making available the public portion of new 10(c)-1 information, which is more comprehensive than existing data, and by making such data available to a wider range of market participants and other interested persons than currently access existing data. This effect could be similar to what was observed with the implementation of TRACE in corporate bonds.” [5]

Studies of the various implementation phases of the TRACE system provide some valuable evidence that mandatory transparency in financial market design can, indeed, increase market efficiency and reduce overall transaction costs.

The proposed regime has a free-rider problem.

In spite of the expected benefits, the start-up and ongoing costs are estimated to be considerable. But the proposed system also has a free-rider problem. As stated above, the bulk of the costs would be borne by lenders and agents, while the benefits of the new transparency would flow to all participants in the securities loan transaction chain. The Commission estimates that startup costs payable by just 409 lenders and agents could total $375 million, with ongoing annual costs of compliance totaling $140 million.

It is true that the RNSA (i.e., FINRA) would incur some costs in establishing and maintaining both the methods of data collection from lenders and agents as well as the infrastructure necessary to make that data available for free to the public. The Commission, however, anticipates that even these charges will be “recouped by the RNSA from market participants who report securities lending transactions to the RNSA” (again, the lenders and agents).[7] In fact, the Proposing Release suggests that the RNSA could itself ask for permission to onsell this transaction information to other vendors (who, in turn, would sell performance metrics and analytics based on the data to market participants like lenders).[8]

Lenders bear the ultimate cost.

If Rule 10c-1 is adopted, FINRA will pass compliance costs through fees to lenders and agents. Lending agents, in turn, will pass the costs of compliance through to their lending clients. Most beneficial owners participate in securities lending to generate marginal income. If lenders are forced to bear the final cost of compliance with Rule 10c-1, they may find their margins so thin that they can no longer justify their lending activities, pulling their liquidity from the market. In addition, with the lenders dependent upon their agents for reporting to the RNSA, it could make it more difficult for lenders to switch agents. This inability to move between agents could weaken lenders’ positions when negotiating fees with their agents. The SEC acknowledges each of these potential outcomes in its proposal in passing as “indirect costs,” and indicates that they are mitigated by other factors like the increased competition between lending programs and between broker-dealers resulting from better access to information.[8]

Cui bono?

The compliance costs of the SEC’s Rule 10c-1 proposal fall squarely on the shoulders of lenders. Will the added transparency and potential transaction cost savings promised by the proposal be worth those costs? If lenders are to benefit from this new transparency, they must realize some appreciable economic gains or material cost reductions to defray shouldering the entire compliance burden.

[1] Rule 10c-1 Proposing Release, p. 10.

[2] According the D.C. Circuit the agency must “apprise itself—and hence the public and the Congress—of the economic consequences of a proposed regulation before it decides whether to adopt the measure.”

Chamber of Commerce v. SEC, 412 F.3d 133, 144 (D.C. Cir. 2005)

[3] Rule 10c-1 Proposing Release, p. 105;

[4] Rule 10c-1 Proposing Release, pp. 79 et seq.

[5] Rule 10c-1 Proposing Release, p. 106.

[6] Asquith, Paul and Covert, Thomas and Pathak, Parag A., The Effects of Mandatory Transparency in Financial Market Design: Evidence from the Corporate Bond Market (April 8, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2320623 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2320623

[7] Rule 10c-1 Proposing Release, p. 69; see also p. 72

“To fund the reporting and dissemination of data provided pursuant to this Rule, the Commission is proposing paragraph 10c-1(h), which would reflect that the RNSA has authority under Exchange Act Section 15A(b)(5) to establish and collect reasonable fees from each person who provides any data in proposed paragraphs (b) through (e) of proposed Rule 10c-1 directly to the RNSA.”

[8] Rule 10c-1 Proposing Release, at note 119

[9] “This may pose indirect costs on these broker-dealers’ and lending programs’ customers. Such costs would include the cost of switching to a new broker-dealer or lending program, the loss of potentially more suitable options for such services if the exiting entity was highly specialized, and potentially higher prices associated with reduced competitive pressures.” Rule 10c-1 Proposing Release, p. 146. See also p. 149 et seq.